At Jeyes on The Square, Earls Barton, we welcome the opportunity to tell the story of 40 years – beginning as a village chemist in 1981 to today’s busy coffee-shop, gift shop and small visitor attraction – but there is a second story, and the history of recycling shows it goes back to ancient times.

In the Eighties, as Jeyes Chemist, Wellingborough Council would, once a week, collect all our commercial waste, charging us through the rates. Then, the local facility was cancelled overnight and we were left carrying the can. We looked to commercial schemes with consideration given to recycling, as The Apothocoffee shop had become a thriving day-time restaurant, with the obvious waste.

For years we persevered with an expensive but hit and miss service, listened to many excuses for non-collections, often featuring broken down vehicles. Being newly accredited with Visit England for our Heritage Centre and Museums – full bins outside were not a welcoming site. Two years ago, we changed to the family business, Cawleys. Their reliability, efficiency, their commitment and guidance to improving our recycling systems have been invaluable. They accepted our openings and closures as lockdown rules dictated with understanding. They have, for us, Put the Waste in the Right Place!

Frank and Reg Cawley, started their civil engineering and haulage contracting company in 1947, in Luton, with Reg becoming sole proprietor in the Sixties. It was a family business then and still is today.

The younger generations of the Cawley and the Jeyes families may claim today’s recycling culture belongs to them, but the first recorded paper recycling was in the paper mills of Japan in 1031. By 1690, in Philadelphia, old fabrics, cloths, cotton and linen were recycled into paper too. In New York in 1776, after America gained independence from the British, King George III’s statue was melted down and converted into bullets for their war effort.

Back in England, The Shoddy Process had begun in 1813 at Batley, West Yorkshire, recycling old wool, clothes and rags to be spun into yarn. By 1860 they were producing over 7,000 tons a year. Five years later, William Booth had founded the Salvation Army, and in 1891 formed the Darkest England scheme, creating Our Household Salvage Brigade sorting and reusing items from the home.

Rag rugs made from old clothing, woollen coats, jackets and trousers, were made each Christmas to lay in front of the fire, before being thriftily demoted to the kitchen, then as doormats, to the dog kennel and ending their days on the compost heap. We have an original rag rug in front of the range in our village Museum in Earls Barton. That is what I call recycling!

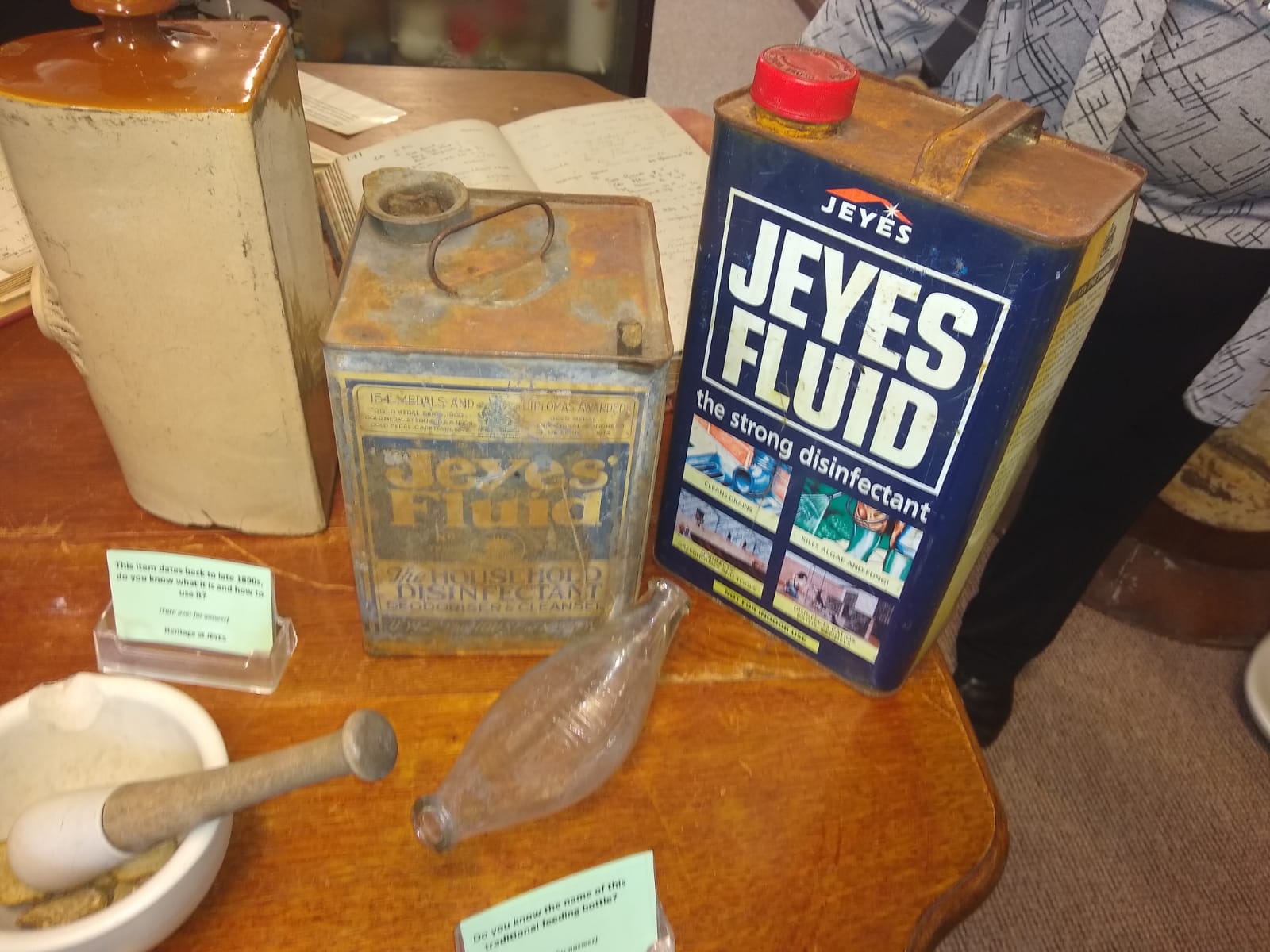

In 1810, Philadelphus Jeyes joined the chemist, Dr Perrin as a pharmacist, druggist, inventor, businessman and entrepreneur at 6 The Drapery, Northampton. Little wrapping or branding was used, with prescriptions secured by a seal. Towards the end of the century there was a shift towards a throwaway society, with grocers and meat vendors often distrusted, so ‘safe’ closed packets, bottles, tins were used and discarded – hence the term Victorian Era Trash. Presentation, marketing and advertising the brand became important.

Parts of London had a systematic disposal of waste but in rural areas it was common for pits to be dug and the waste buried.

Philadelphus’ younger brother, John, was a botanist, nurseryman, analytical chemist and inventor. He left for the Victorian slums of London, armed with his many disinfectants, including Jeyes Fluid – The True Germicide, The True Disinfectant, The True Antiseptic. His wish was to help cleanse and prevent the spread of disease caused by the vermin feeding in the festering rubbish. 35 folk and their pig would be living together, emptying their own waste down the cellar (or the neighbour’s) into the Thames below. (Not to be recommended for their supply of drinking water!)

During both World Wars the public were canvassed to help – even waste cooking fats went to local meat dealers to be recycled to fund explosives. There was an attempt to requisition the famous Implement Gates of the Jeyes Family Home, Holly Lodge outside Northampton but they were spared and are still there today.

In the Sixties, Seventies and Eighties, drinks companies (I remember the Corona pop man coming on his rounds) offered money-back schemes – charities benefited and it was a rich source of pocket money.

The iconic logo as The Universal Recycling Symbol, still used today, was designed in 1970 by 23-year-old Gary Anderson, an engineering student in California after he entered a competition and won.

In June 1977, Stanley Race CBE, as Chairman of The Glass Manufacturers’ Federation, dropped the first glass jar into the Bottle Bank in Barnsley, South Yorkshire – he repeated the task 30 years later. There are now more than 50,000 banks with 752,000 tons recycled annually.

Following new rules and a 5p per bag charge in 2015, plastic bag use in England was reduced by 80%.

Today, as I write, I have wasted not or wanted not, but having started the day as a conscientious shopkeeper supporting recycling, and now, having been challenged by the significance of my research, feel I am entitled to call myself an older and wiser garbologist.

The Cawley Family continually endeavour to put recycling at the forefront of their work ethic whilst the Jeyes Family know they can trust and rely on them, working together in the future.